When the lease contained in a property transaction is identical to market terms and conditions, the net value of the lease is zero; and the value of the leased property is equal to the fee simple value of the property.

Valuing real estate for ad valorem purposes is becoming even more complex as assessors and property owners fight over definitions and the valuation procedures associated with those definitions. To assist in this discussion, this article describes the terms, conditions and procedures that are necessary to achieve proper valuation for ad valorem purposes when the standard for valuation is the market value of the fee simple interest.

There are two primary issues at hand in this discussion: the transfer of property rights and highest and best use (HBU). Before HBU can be thoroughly discussed, the transfer of property rights must first be determined. When valuing property for ad valorem tax purposes, the market value of the fee simple interest is (usually) needed. The fee simple interest is a freehold estate in real property ownership. The term “fee” means that an ownership interest in land and all attached to the land is inheritable, and fee estates are “freeholds” which means that the fee interest is either uncertain or unlimited in duration. Historically, the terms fee and fee simple are interchangeable and therefore equivalent, and the first discussion of leased fee refers to the ownership of the fee interest when a property is leased was in 1926.

2. This evolved into the term “leased fee” that appraisers use today. The fee simple interest (or simply, the fee interest) is considered the greatest type of interest in property ownership available and is often termed the “fee simple absolute estate.” What this means is that the fee simple absolute estate (interest), the fee simple estate (interest), and the fee estate (interest) are synonymous terms and indicate the same thing—the greatest possible ownership of a land parcel including all the rights, interests, limitations, obligations and improvements to that land parcel.

When transferring ownership of the property, a warranty deed will not only include the names of the grantor and grantee, the physical description of the property, and consideration of the grantee and words of conveyance by the grantor, it will also include any appurtenances and hereditaments of the property, including leases which are termed quasi-personality.

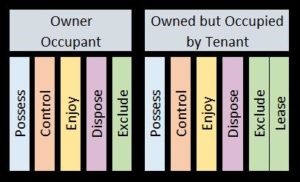

3. In addition to recording deeds for the sale of real property, many states also require leases to be recorded to give official public notice of such transactions, and the recordation order for these public documents is specific. Regarding recordation in the case of a sale-leaseback transaction, the real property deed is recorded first and the lease is recorded afterwards. This is necessary to ensure that the true parties to the subsequent lease are properly reflected in the titled ownership of the estate in real property even though both are executed together at a real estate closing. These issues are extremely important considerations in the valuation process for leased property since the real property bundle of rights associated with leased property transactions must be addressed and recognized properly. In the chart below, the bundle of rights and obligations—both real and personal—associated with an owner occupied property are compared to the bundle of rights and obligations of a leased property (owned, but occupied by a tenant).

Figure 1

Ownership Rights for Owner Occupied and Leased Property

The typical bundle of rights associated with the fee simple estate (owner occupied) include the right of possession (the property is owned by the title holder), the right of control (the owner controls the property’s use), the right of enjoyment (the holder can use the property in any legal manner), the right of disposition (the holder can sell the property), and the right of exclusion (the holder can deny people access to the property), among possibly other rights. It is when a property is leased to others that an additional personal property interest is created—this is the lease contract interest in the property. This lease intertwined with the real property right of exclusion in the fee simple bundle of rights through proper execution. This is why the lease is termed a quasi-personality. In other words, the right to exclude remains with the bundle of rights transferred in a property transaction because the specific terms of exclusion giving the tenant temporary occupancy of the property (the quasi-personality) are present in the lease contract that is assigned during the property’s conveyance along with the remaining bundle of rights in the deed.

As depicted in Figure 1, the lease contract does not remove any rights from the bundle of rights of the fee simple estate, but rather it is an addition to the fee simple estate. This is evidenced by the fact that whenever a property that is currently leased is sold from one party to another, the new owner (the grantee listed in the deed) obtains not only the full bundle of realty rights associated with the property, but also the quasi-personality interests and obligations of the lease. The right to exclude others is conveyed to the new owner through the lease that is part of the bundle of rights contained in a leased property’s transfer, and, upon termination of the lease contract, the right of exclusion is no longer governed by the lease but is held exclusively by the owner of the estate in real property—the grantee of the conveyance. An example of this process is developed and explained later.

The bundle of rights depicted in Figure 1 is also consistent with generally accepted appraisal practice where leased properties, whose contractual lease terms are at market levels, are said to have a value that is at “market,” or is numerically equivalent to the fee simple value of the property. It is also maintained by the appraisal profession that even though the value of the “leased fee” property is equal to the “fee simple” value of the property, conceptually the two real property interests are different. This second statement is not true because the leased property has the same bundle of real property rights as a fee simple property. The leased property simply contains an additional set of personal property rights and obligations that exist in the lease contract, but the real property rights of possession, control, enjoyment, disposition and exclusion all exist and are conveyed and/ or assigned from the grantor to the grantee. This means that the same set of real property rights can exist in all conveyed properties regardless if they are leased or owner occupied, and if the purpose of the appraisal assignment is to value only the real estate the appraiser must simply remove the incremental value of the personal property component (i.e., remove the net value of the lease). When the lease contained in a property transaction is identical to market terms and conditions, the net value of the lease is zero; and the value of the leased property is equal to the fee simple value of the property.